Child poverty is multi-dimensional

Across the world you are more likely to encounter children living in poverty than you are adults.

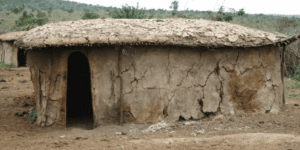

Poverty impacts children’s lives in several fundamental ways. For example, a child can be deprived of the basic right to education. In addition, limited or no access to healthcare in any form is widespread, and countless children are deprived of everyday things that many people simply take for granted, like clean water, food (not to mention a healthy, balanced diet), even a safe place to shelter and sleep. Needless to say, life without necessities such as these is extremely dangerous to anyone’s wellbeing, violates a series of human rights, and beyond the physical impact undermines mental wellbeing and self-esteem. Moreover, the consequences of such child poverty are likely to undermine any prospects for the future, and can last for years, or even an entire lifetime.

UNICEF’s definition of child poverty

NGOs use a variety of statistical techniques to reach bold definitions of poverty and child poverty. They also offer estimates of the number of children who live in absolute poverty.

Anyone who lives on an income of less than $2.15 a day is considered to be in extreme poverty. Of course, the cost of living varies hugely around the world, but suffice to say that in any context that sum does not stretch far. Behind this financial definition lie all sorts of deprivation, caused by many socio-economic factors arising from wars, the breakdown of communities, political unrest, natural disasters, global warming, no social security, lack of infrastructure, etc. Perhaps the most significant factor is the sheer lack of opportunity for children who live in poverty, and hope for self-improvement.

UNICEF calculates that across the world approximately one billion children live in poverty, meaning that they have limited or no access to the fundamental necessities listed above. Of that number, researchers suggest that about one third of a billion children live in absolute poverty, meaning that they and their carers (if they have carers) must try to survive on less than $2.15 per person per day. Geographically speaking, a majority of children living in extreme poverty are to be found in sub-Saharan countries. That said, even in high income countries there are children who live in poverty.

The toughest places to survive to age five

The toughest places to survive to age five

Statistically, it is where children are born that dictates the probability of their survival to their fifth birthday. UNICEF-endorsed research presents data from 196 countries. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in places such as Norway, a child has a 999/1000 chance of surviving to and beyond their fifth birthday. In Singapore it’s 998/1000, in European countries like Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Spain it’s 997/1000, while just across the English Channel in the UK, it’s 996/1000. Yet at the other end of this contrasting data spectrum, survival chances in Somalia are 894/1000, in Nigeria 893/1000, and in Niger 883/1000. To put that another way, in England children have less than 0.1% chance of dying before their fifth birthday, while in a sub-Saharan context like Niger, it’s about 12%. And because of wealth imbalance and its consequences across communities these figures are far higher in particular local contexts.

Some consequences

Children who live and grow up in extreme poverty face grim challenges which impact their physical and cognitive development. Naturally such a lifestyle means a harsh outlook for the future, at the least restricting opportunities for employment and self-improvement. UNICEF research concludes that, ‘children who grow up in poverty suffer from poor living standards, develop fewer skills for the workforce, and earn lower wages as adults. This is why, in the absence of sufficient programmes to address it, poverty tends to persist from one generation to the next.’

How Child Poverty can be tackled

How Child Poverty can be tackled

NGOs like Save the Children and UNICEF tirelessly campaign to bring an end to child poverty. Governments can introduce programmes to tackle poverty at a grass roots level. These include social security measures like health insurance and provision, personal cash transfers, school fee waivers, and maternity support and benefits. In countries where such support has been introduced there is powerful evidence that the causes of poverty can be successfully tackled and reduced.

UNICEF has introduced rolling programmes in many of the world’s poorest communities to offer social protection, education, health and nutrition support to children who are among the world’s very poorest. There are sanitation and clean water programmes which are vital to help keep people safe from avoidable but all too commonplace illness.

NGOs also respond quickly to natural disasters with lifesaving emergency aid. Moreover, UNICEF promotes initiatives alongside governments and other partner organisations to undertake thorough research which measures and assesses child poverty. Without the data produced, political intervention would be far less targeted and effective. The World Bank also backs statistical research which leads to better informed policy discussion and decision making. This means smarter investment and ultimately more effective social support for children who live in extreme poverty, as well as for their carers. And ultimately it is why the numbers of children living in extreme poverty – while still overwhelmingly huge – are now consistently falling year on year.

In conclusion, continuing to raise awareness through platforms like Poverty Child’s is crucial in tackling child poverty and accelerating the drive to end it.