UNICEF’s four key policies to end child poverty

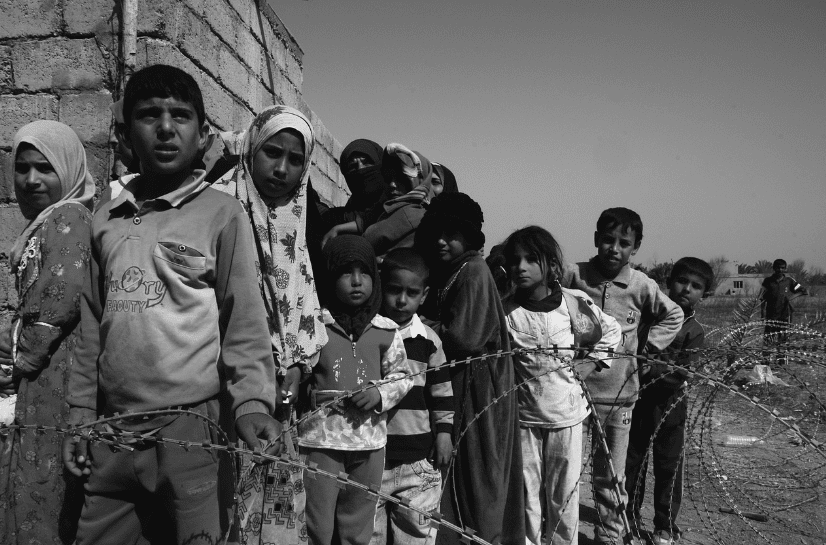

UNICEF has recently relaunched four proven policy solutions aimed at transforming the lives of the 900 million children who presently live in multidimensional poverty around the globe. Each of these policies has been devised from in depth, evidence based research. Their collective mission is to deliver efficient progress towards the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and so further reduce child poverty.

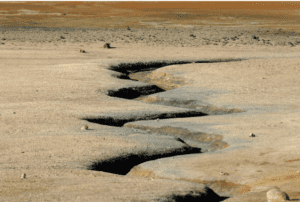

UNICEF’s Executive Director, Catherine Russell, endorsed the initiative, “It is imperative that we ramp up actions, and investments, to strengthen systems that children rely upon, like health care, social protection, nutrition services, education, water and sanitation.”

One: roll out more immunisation programmes

One: roll out more immunisation programmes

In the last 50 years, it is suggested that by rolling out vaccination programmes the lives of 146 million under fives have been saved. That is about twice the entire UK population. Such an impact has contributed to a forty percent reduction in child mortality. The upscaling of vaccination programmes is remarkable. UNICEF confirms that global outreach expanded from twenty percent coverage of young children in 1974, to eighty five percent by 2023. In just under half a century that is well over a four hundred percent increase in the number of infants vaccinated against life threatening, yet preventable, diseases. If all countries were able to fulfil the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of ninety percent coverage by 2030, that would mean about 51 million child deaths would be prevented. And that would be 51 million fewer, preventable bereavements. Beyond the natural joy of babies and young children surviving and potentially thriving, there are also financial, personal and community benefits. UNICEF suggests that for every dollar invested in vaccination programmes there is likely to be a return of $21 in economic terms for communities within developing countries. That could, and should, prove transformative.

Two: address child nutrition and development in early years

Two: address child nutrition and development in early years

Around the world, twenty percent of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition, a condition also referred to as stunting. That is about 150 million children. Moreover, almost one third of children between the ages of three and five are, developmentally speaking, not on course. Equally shocking is the fact that approximately 136 million five to ten year olds are clinically overweight, or obese.

That said, there has been considerable progress over the last three decades in addressing these issues. Since the mid 1990s chronic malnutrition has been reduced by over forty percent. The total number of children with stunted growth and under development has officially reduced in those thirty years by 110 million.

UNICEF has established a global target to ensure that half of all babies are breastfed by the end of 2025. If countries were able to promote and attain that goal child malnutrition would continue its steady decline. In addition, there is a potentially huge financial benefit for developing countries. It is estimated that more than $300 billion would be generated because of improving child survival rates, and better nutrition. It would lead to generally stronger physical and cognitive development among children and young people. Researchers calculate that for every dollar spent in the promotion of breastfeeding there would ultimately be a resulting economic benefit of at least $35.

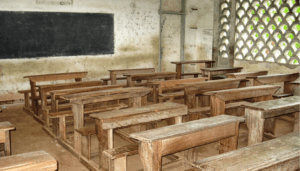

Three: enshrine education for girls beyond primary school

Three: enshrine education for girls beyond primary school

There follows another sobering statistical fact. UNICEF records that around the world there are currently 119 million secondary school aged girls who are not in education. Approximately one in four girls and young women aged 15-19 are out of school. That poignantly contrasts with ten percent of boys of the same age. In the majority of cases these girls are destined for early marriages and early motherhood. Yet the UN’s researchers confirm that an investment of about two dollars a day per child can make an astounding economic impact. Were these girls to remain in secondary education and acquire high school qualifications, knowledge and skills, they could collectively contribute up to ten percent of a developing country’s economic growth.

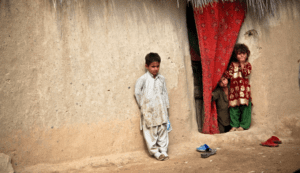

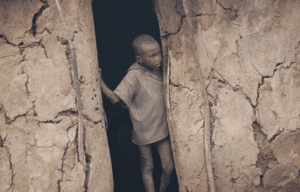

Four: introduce social protection and financial support for children

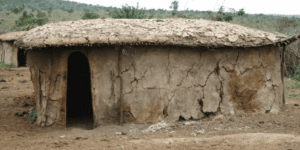

It isn’t far short of one billion children who live in multidimensional poverty. As I have stressed in other blogs, if you were to travel around the globe you would be considerably more likely to encounter very poor children than you would adults. Almost a third of a billion of those children live in extremely poor households, makeshift shelters or simply on a street. They survive on $2.15, or less, each day. Many spend their time begging or searching for any source of food or income. Given that, it is extraordinary to note that less than four percent of funds used globally for social security and state benefits is spent on children. Almost two billion children and young people under the age of eighteen have no ready access to such financial lifelines.

International comparisons demonstrate the stark contrast between communities which have financial support for children and those that do not: they are much poorer. Typical poverty rates in a country where there is no social security cash benefits for children are over thirty three percent. However, a country which makes child benefit cash payments has, on average, poverty rates that are around sixty percent lower.

In conclusion, committing to UNICEF’s four proven policy solutions will help to reduce and end multidimensional child poverty faster and more effectively. It is worth remembering that at a time when countries are reviewing overseas spending budgets, the means to end child poverty for good have never been more tangibly close to hand.