Why children’s views matter when assessing child poverty

When it comes to defining and researching child poverty on a national or global basis, it might strike some people as counter intuitive to involve children in the preparatory groundwork at all. Yet by consulting with children and young people in a meaningful and engaging way, they are likely to feel empowered by the process and become engaged with it. Moreover, they may sense that their rights, as well as their views, are being respected. What better way is there to represent the experiences and opinions of children concerning their own circumstances. In estimating differing levels of poverty and differing needs it may in fact be of paramount importance to take into consideration the views of children.

An example of a child-centred approach to analysing child poverty

A study from 2015 attempted to examine the priorities of South African children who were living in poverty by asking them to formulate and then subsequently arrange an itemised list of commodities, services and everyday essentials onto a scale between what they considered an absolute necessity through to an out and out luxury.

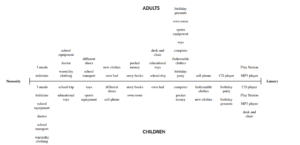

Those children undertaking the surveys were first asked to compile a list of essentials for their day to day lives. The top 25 choices were selected for the comparative survey. The results are shown below in table form and contrast with sample responses from adults who were asked to perform the same exercise.

(Barnes, H. and Wright, G. (2015) Defining child poverty in South Africa using the socially perceived necessities approach. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/reports/world-free-child-poverty)

Contrasts and similarities

Of the 25 items on the list, only six coincide in the priority ranking from both the adults’ and children’s surveys: three meals a day (1st), toiletries(1st), storybooks(5th), a computer (7th), a Play Station (10th) and an MP3 player (10th). Perhaps it is unsurprising to see the four items which coincide in first and tenth positions.

More interesting are the items with contrasting rankings, for example, adults placed new clothes 4th, whereas children voted them 8th. Does this say something about self-esteem from these differing vantages? Conversely a mobile phone was rated 4th by the children, and 8th by the adults. That result may reference universal issues of utility, practicality, cost, and a sincere desire to be connected to the world beyond home. From a young person’s viewpoint, perhaps having personal access to the internet and social media is likely to seem more important than having their own bed or room because of the broadening and aspirational appeal of a phone. A desk and a chair are ranked 6th by the adults and 10th by the children, which implies that children are happy to work anywhere that is available, convenient and reasonably appropriate.

Educational toys (2nd and 6th), and toys (3rd and 7th) are also ranked in marked contrast by each group. Once again, the educational significance and (in the latter case) the social and cultural value of these commodities should not be underestimated. These five examples speak loudly about differences in perception that children may have when it comes to assessing and evaluating what matters to them most in their everyday lives. It might also say something about their ages. There is, however, the vital matter of the children’s first-hand experience, which chimes with the positioning of school transport (1st and 3rd). For a child trying to get to school that selection affirmingly amounts to a top priority, of equal necessity to having access to a doctor. It also sheds light on the child’s perception of the importance of school, especially given the equal ranking of school equipment.

Therefore, it is little surprise, given the above, that children voted the school trip 2nd, while adults considered that much less of a necessity (5th). Another marked contrast is sports equipment (like toys, also 3rd and 7th), which, importantly, may be linked as much to aspirational motivations, as to notions about the beneficial nature of exercise.

What these results show us

Results, such as this table highlights, confirm that there can be a significant difference in the values which children and adults place on everyday essentials, fundamental services and commodities. It would be intriguing and informative to run this sort of exercise on a cross-cultural, global scale.

Implications for future research and programmes targeting child poverty

When it comes to tackling child poverty, taking children’s views into account is not only morally worthwhile, but it is also potentially ground breaking. This is because it is likely to prove genuinely insightful when evaluating their needs and values, and therefore help to shape the form and goals of future assistance. If decisions about issues like these are simply taken by adults then it is highly probable that the outcome will transpire be partly at odds with what really matters to the children in question. And in turn, those children are likely to wonder how and why such a programme was designed in the first place, and reflect on how beneficial it is to them. Developing an effective campaign to address child poverty is likely to benefit from an inclusive approach which embraces the opinions and values of the people for whom it is essentially intended. In other words, alongside evidence backed views of politicians, researchers and managers at non-government organisations (NGOs), relief agencies and charities, it is equally important to take into consideration children’s opinions about their own needs and values.