A recent UNICEF report explores what happens to children and families when a humanitarian crisis strikes their community leaving them without access to good quality, affordable childcare services.

The number of children living in a humanitarian crisis

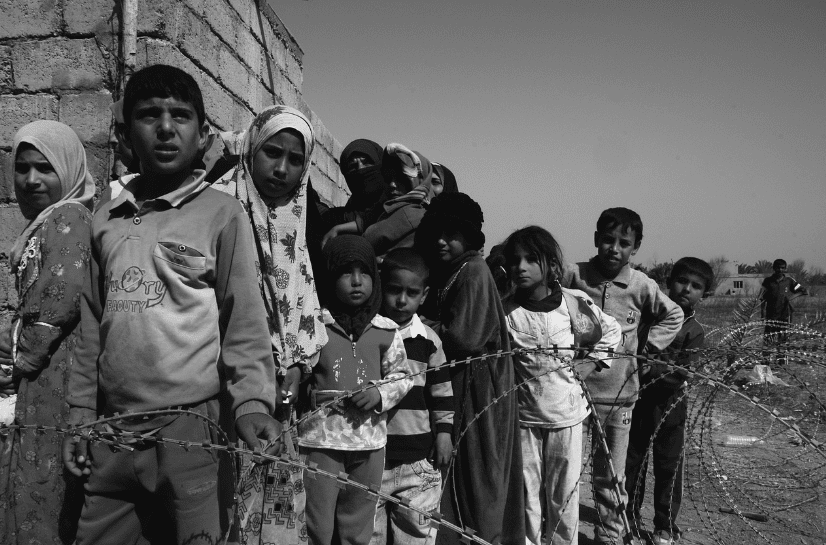

UNICEF estimates that around the globe approximately 59 million children are presently living in a humanitarian crisis. That is about the same as the entire population of England. Of these, a bewildering 31 million have been forced to move away from their homes.

Factors adding to these numbers

There are several ongoing conflicts across the world which have added significantly to these numbers, as has the global pandemic, and environmental events related to climate change.

How many children living in developing countries attend early years care?

How many children living in developing countries attend early years care?

About 70% of children, aged three – five, who live in a developing country, do not attend early years care. The number is naturally higher in countries where there is an ongoing humanitarian crisis. And it is much higher in all contexts for infants under three years old.

This matters because childcare offers an array of positive opportunities to enhance and prompt brain development. Beyond socialising, it affords chances for children to explore their personalities, and refine skills which will help them in subsequent educational programmes. For example, they learn how to interact with others and gain confidence in fundamental interpersonal skills, develop their ability to concentrate on challenges, empathise with others, and recognise boundaries and self-control, while developing language skills. All that can be stimulated by carefully designed play-centred activities.

Interaction with other children and staff is central to enhancing personal development. Children also learn practical skills and gain a sense of self-esteem. Experiences that children have while attending childcare programmes can make the difference between their establishing robust or fragile foundations for the future.

The disruption caused by a regional crisis

The impact and aftermath of traumatic events such as conflict, a natural disaster, forced displacement, bereavement, or political upheaval within communities is almost always detrimental to children’s personal, social and educational development. UNICEF describes a neuro-biological toxic impact which is potentially harmful to young children’s cognitive development and brain function. It is argued that toxic stress can adversely affect mental wellbeing as well as physical health. This in turn can impact long term on the educational progress and personal development of young children. Regrettably, effects from traumatic events and disasters can even permeate through to the next generation.

If a young child’s experiences are shaped by traumatic events their self-confidence can be rendered fragile and their personal circumstances may even mean that formal education becomes a remote option. This may be because the education system is seriously disrupted or because there is a need for children to remain at home to support their mother as caregivers to elderly relatives or younger siblings. Moreover, events which undermine opportunities to enjoy childcare programmes deny children the chance to learn about themselves, restrict their chances to interact and empathise with others and, in short, hinder children’s personal development. This can even affect their outlook on, and approach to, being parents themselves.

The prohibitive cost of many programmes.

The prohibitive cost of many programmes.

Tens of millions of mothers find it difficult to access a good quality, affordable childcare programme. As a result UNICEF confirms that women spend three times as long looking after young children than men do, and the disparity in such a role has become more marked during and since the pandemic, because so many childcare providers closed for good. This discrepancy explains the domestic existence which a majority of women around the world experience. Prior to Covid-19, 52% of women stayed at home as primary caregivers, whereas 25% of men did so.

The economic consequence

Acting as a non-earning caregiver means that women are more than twice as likely as men to be living in extreme poverty. As they are not wage earners, these women may well feel subservient to their husbands or partners, and be fully dependent on them.

The benefits of childcare for mothers and domestic caregivers

Childcare offers an opportunity for respite and frees up time to carry out other important tasks or access vital services. This may well include tasks which are simply not conducive to offering childcare at the same time. It also allows mothers and care givers some time to destress from the trauma of the crisis and assess how best to carry on. This is crucial for the mental wellbeing of domestic caregivers. It also means that they are likely to be better caregivers at other times.

Why provision for quality childcare in humanitarian crises is a priority for all

Why provision for quality childcare in humanitarian crises is a priority for all

It isn’t just about the undoubted benefits to the children and parents concerned. UNICEF has published research which estimates that each dollar invested in childcare programmes yields a financial return in the range $6-$17 in economic benefits to society as a whole.

The importance of childcare in a crisis

In a time of emergency, a majority of mothers and domestic primary caregivers will likely have few resources, time and even a safe place to devote to offering young children some educational experience. If the crisis involves violence, the breakdown of law and order, or forced displacement, then childcare provision may be very limited. However, if NGOs and charities are able to promote some childcare provision, that will automatically establish a sense of routine for the children and their parents, and afford a safe environment for everyone involved.

The impact of neglect or abuse on children experiencing a crisis

The impact of neglect or abuse on children experiencing a crisis

There seems to be little doubt that children facing a humanitarian crisis are more at risk of abuse or neglect. These factors have a detrimental impact on children’s personal, mental, cognitive and physical development.

Good quality childcare provision helps to temper the effects of neglect and therefore reduces the risks of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and below average growth rates.

Moreover, a programme of childcare can be used as a conduit for rolling out other services to children and their parents. These include basic medical services, hygienic sanitary facilities, support with nutritional aid alongside early education.

During a crisis women benefit more from childcare provision than men

In a humanitarian crisis there tends to be an increase in women who act as the head of their family. This may be because husbands, brothers and sons have been compelled to leave home in search of employment or been required to be away from home in the immediate aftermath of the disaster. Therefore, it is often mothers who experience increased vulnerability just as they are forced to assume greater responsibility. They will certainly find it difficult to locate basic services let alone a childcare programme, which could free up valuable time, as well as holistically benefit young children. After all, domestic childcare is a full time role.

The role of girls

If a mother is able to find work, it would usually be an older daughter who assumes responsibility for looking after her younger siblings. This could well mean that she has to abandon her own school career which in turn will harm her future employment prospects.

A secondary school age education is the proven best way to empower children to lift themselves out of poverty. It also delays the prospect of marriage and starting a family. UNICEF argues that girls are likely to enjoy more personal benefits from attending secondary school than boys. Moreover, mothers who have themselves completed secondary school education are statistically more likely to send their daughters to secondary school than mothers who left school early.

Conclusion

Establishing childcare provision during a humanitarian crisis ultimately brings benefits to everyone in the community. In the short term it will add a sense of routine, free up time and space, as well as bring educational and personal benefits for the children. In the long term, however, it will contribute to lifting people out of poverty and that is the most important justification for establishing childcare programmes for displaced families facing a humanitarian crisis.