Armed conflict can be one of the most destructive events known to humankind. From the stone age until the present day, wars have been fought over resources, territory, power, and riches in an almost constantly recurring cycle. It damages infrastructure, topples economies, destroys social networks, and has particularly harmful consequences on children and young people regarding their well-being and development.

However, whilst wars and conflicts have always raged there has invariably always been a distinction drawn between combatants and civilians[i]; a bargain struck so that the most vulnerable of society would be granted immunity from the horrors of war. Unfortunately, this sentiment does not represent the realities of war, nor how those most vulnerable often act in the face of conflict – in particular, how children act.

Children in modern conflicts have unfortunately become intrinsic to warfare and how it is waged with the most basic laws of the Geneva Convention being violated in every major warzone as children are targeted in efforts to inflict terror on populations. This callous tactic not only poses a severe physical threat to children, as they may be killed or injured but also a psychological threat to wellbeing and life post-war. What has become most worrying in modern times is how the impacts of conflict do not always affect children as passive actors. In many countries where war is present, children are increasingly assuming more active roles in the conflicts that persist in their communities.

Children brandishing arms is indeed by no means a new development. The Spartans took boys from their family homes at the age of seven to train in the military whilst the Ottoman Empire stole children from its subjects in the Balkan states to fill out the ranks of its Janissary army through a system referred to as the devshirme[ii]. In more recent history, when the Iranian regime began to falter in the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s children from the ages 12 upward were called up to fight Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the new ‘Holy War’[iii]. But in present times, the training and use of child soldiers has become more commonplace than ever.

In 2017 it was estimated that more than 100,000 children were currently being forced to play active roles in conflicts[iv] in the fifteen UN-identified countries Yemen, Somalia, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, Colombia, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Sudan, the DRC, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Syria, the Philippines, and the Central African Republic. However, these are only the recognised countries and there are many more nations where groups are suspected of cultivating children as active participants in violence and crimes across the globe; even in some Western countries where terror cells, separatist groups and nationalists lurk beneath the visage of peace.

Today most active child soldiers are enlisted in rebel militia groups in developing nations in Africa, Asia, and South America. Militia groups often rely on a steady stream of voluntary recruits to sustain their operations. But when this voluntary stream runs dry some do resort to forced recruitment – a strategy that has become particularly prevalent among those groups that operate with children in their ranks. The extent and scale of this recruitment can, and does, differ between groups as conflicts run their course as some may employ children for individual missions whereas others will utilise them throughout.

It is important to note that this is not a problem limited to young males. The role of child soldiers is played by both boys and girls; and whilst it is commonly assumed that children recruited by militia groups are automatically handed weapons and trained as soldiers, it is not always the case. Children often take up other roles within these groups such as cooks, spies, or messengers. Young girls are particularly vulnerable when recruited as they can also face the burden of sex work resulting in physical and mental damage that lasts a lifetime even when emancipated. Regardless of how they are recruited or what role they play, child soldiers are victims of war and poverty. A child enacting a role that does not send them to the front lines of a conflict is still exposed to varying levels of violence, abuse, risk, and hardship – even though it may take different forms.

But what is most worrying about the current station of child soldiers is that not all of them are taken by force from their domiciles, or even coerced. A large quota voluntarily join armed conflicts with little resistance. The reasons for this all link back to poverty and deprivation in times of conflict.

Recruitment vs Voluntary Conscription

Whilst many children are recruited by armed groups, it is not enough to simply condemn those groups responsible for recruitment; especially when it is also the case that many children voluntarily and willingly join up. Children who join armed groups voluntarily are often already experiencing the impacts of war or conflict which can push them towards fighting. Traumatisation and brutalisation are two key experiences that push some children to join up. Children can experience high levels of trauma when witnessing violence through shelling strikes, shootings, landmine explosions and other atrocities in their communities that provoke them to conscript with armed groups to fight back – whether against a civil enemy of one further afield. Similarly, brutalisation is experienced as children are targeted by warring factions and are subject to search operations, improper detention in unlawful circumstances and sometimes torture – all of which contribute to a decision to fight the perceived inducer of these experiences.

But the main contributing factor that pushes children and young people to join armed conflict is deprivation and poverty. Families who have been displaced by conflicts and who are lacking income, jobs, food, and other necessities for survival often encourage children to voluntarily join armed groups as a way to make ends meet in extreme circumstances. Employment in armed groups affords children the potential for a roof over their heads, food, and, to a lesser degree, protection from the war outside. The choice to fight therefore becomes a plea to change their position in society and improve their opportunities for growth and development – or rather, at least it is perceived that way. The reality when living and participating in armed groups is often far different.

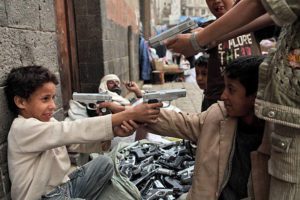

But what if war hasn’t devastated a child’s home; why do they then still choose to conscript? An answer for this lies in the Middle East at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, in Yemen. Yemen is a country whose civil war has been ongoing since 2014 and child soldiers have become an intrinsic part of the Houthi rebel group’s (and to a lesser extent government forces too) tactics. Since 2015, there have been nearly 4000 verified child soldiers active in the region[v] – with the actual unverified number expected to be much higher. The UN says that over 10,200 children have been killed or maimed in the war since its start nearly a decade ago which has pushed many others into the fighting. But what is most concerning, however, is the unusual socially prescribed relationship young men and boys have with guns.

Acquiring and owning weapons is engrained in Yemeni culture historically[vi] and the link between gun ownership and manliness is an intrinsic part of Yemeni tradition that has stood for hundreds of years. Even before guns, men used to carry curved daggers known as jambiya as a sign of strength and manhood. Firing guns in celebration of weddings, birthdays and more is common practice and a sign for rejoice among many. But whilst traditional tribal law prohibited the use of these weapons by and against women and children, these rules have been bent and broken over the last decade, especially with young boys.

The eternal pairing of weapons and manliness has resulted in the self-arming of many young boys who visualise their coming-of-age with fantastical ideas of guns and masculinity reinforced by a needless war that only provokes conscription to armed groups. For Yemeni boys, not having a gun would lower their status in social circles and limit their opportunities for development whilst transitioning into adult life. It is therefore as intrinsic a possession as the shoes on your feet and is why the country has such a prolific gun culture. There are an estimated 2 guns for every 1 person in the country with a population of roughly 23 million[vii]. Focussing the blame onto rebel groups, therefore, ignores the systemic problem that causes voluntary conscription in the first place and ignores an opportunity to challenge the issue at its roots.

The Dar Al-Salam Organisation: منظمة دار السلام (DASO) – or ‘House of Peace’ in English – is an indigenous Yemeni non-governmental organisation (NGO) focused on conflict resolution and disarming practices. The organisation has developed over 250 grassroots peace committees across the country working with over 4000 tribal leaders to conduct multiple youth peace-building workshops across the country. The workshops aim to promote the ethos of peaceful coexistence as an alternative to war[viii] to combat the doctrine of guns and manhood among the country’s young boys (and girls, although to a slightly lesser extent). The organisation also runs campaigns to stop youth conscription into violence to prevent further young people from involving themselves in the war.

But whilst campaigning and education on disarming practices are pivotal to the country’s fight against gun culture and child soldiers, the problem persists. As a result of the war, children experience issues of traumatisation and brutality as a common occurrence whilst also experiencing deprivation and poverty. All this pushes people to sign up to play more active roles in conflict – a position only reinforced by Yemen’s deeply enshrined hegemonic gun culture. This unfortunate cycle of adverse experiences only serves to push more young people into the midst of war and conflict. But despite now having a position to earn both economic and social capital, the experiences of children in these situations are far from improved.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

The experiences we have in our early life, particularly those in childhood, play a significant role in individual growth and development. Both our physical and mental health; our behaviour and emotions; and our ability to form meaningful attachments and relationships can be drastically altered and impacted by our situational experiences both as a child and in later life.

The concept of adverse childhood experiences or ACEs is central to a discussion about child soldiers. The concept defines and encompasses the potentially traumatic experiences that some children live with between the ages of 0-17. The term incorporates various experiences, including domestic abuse, neglect, witnessing and partaking in violence; substance misuse, mental health concerns and consistent instability in the home and the community[ix].

Whilst the impacts of ACEs are significant while young, people who experience ACEs in early life often suffer from the adverse effects of it in later life – particularly with their mental and physical health. People often suffer from an increased risk of certain health conditions in later life such as heart disease and cancer whilst also experiencing greater levels of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety – of those people who are diagnosed with mental health conditions in adulthood, 1 in 3 have previously experienced ACEs[x]. ACEs are also linked to issues of toxic stress (both as a child and as an adult) which can have adverse effects on various aspects of a person’s life[xi], including a further risk to physical health.

Poverty is itself an ACE. Children living in poverty are already at greater risk of experiencing significant physical and mental health problems which negatively impact their well-being. Poverty brings with it a multitude of economic and social insecurities such as lacking the necessary resources to feed or clothe oneself efficiently, heat their home, or properly engage with wider social actors resulting from inefficient opportunities to socialise and social stigmas and labels of the poor. The effects of poverty on a child are devastating on their own but when combined with localised violence and crime, the impacts can be even greater.

Most importantly, children who experience a combination of ACEs and poverty can have their integral understanding of social interaction thwarted and often struggle to understand various emotions (both personally and when exhibited by others). This makes it extremely complicated to process thoughts and feelings both as a child experiencing ACEs and as an adult. Young people experiencing ACEs often, therefore, find it hard to form attachments with others. This can be the result of an unsafe home ensuing from neglect or abuse but can further translate into wider social interaction. When lacking attachment, people are known to struggle as we are inherently sociable creatures[xii] and this is a key contributing factor as to why some children voluntarily join militia groups or gangs. These collectives can provide children with the support and attachment missing from their lives growing up experiencing poverty, neglect, and various other ACEs in the home. If voluntary, joining an armed group like this can instil a sense of connection and attachment that is otherwise vacant in the lives of impoverished children[xiii]. However, the reality of life inside an armed group is far from this and often involves the experience of multiple other ACEs.

How do ACEs Affect a Child Soldier’s Development and Adult Life?

The ACEs that children experience whilst playing their role in warfare are proven to drastically impact their psychological and social development whilst young and leave long-lasting legacies on their mental and physical health as they grow up – some of which are gender specific.

Whilst acting as soldiers, children face various ACEs such as a loss of access to school and healthcare, poor access to food and suitable shelter, forced displacement, and separation from family[xiv]. They further witness and endure physical and sexual abuse. But the most traumatic ACE that affects children both as active and passive actors in armed conflict is witnessing, and partaking in, violence. Children in militia groups are routinely exposed to varying levels of death and injury in war. Some experiences come from the side-lines, acting as medics to injured peers, others come looking down the barrel of a gun on a battlefield. Regardless of how they may be experienced, witnessing such atrocities causes significant harm to children while still serving in armed groups and for a long period after adulthood.

The psychological distress of fighting in wars is well documented with various studies concluding a strong link between the violence experienced in combat and the diagnosis of multiple different mental health concerns such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[xv]. But how experiences of conflict operate in the psyche of children post-war is not as widely understood. Both adult soldiers coming home from combat tours and child soldiers in post-war situations experience psychological issues exhibited in sleep disturbances, eating disorders, aggressive behaviours, and a dramatic increase in suicidal behaviour maintained by high levels of toxic stress. Individuals are unable to turn off their body’s fight or flight response to previously experienced stressful situations and therefore exist in a constant state of stressful anxiety. This is particularly potent among children who have experienced multiple ACEs and is especially evident among ex-child soldiers.

For example, between 1991 and 2002, Sierra Leone experienced one of the worst civil conflicts in recent history that displaced over 75% of its population[xvi] resulting in both a poverty and refugee crisis. The conflict was notorious for the roles that children played throughout whether as combatants or in other positions. In 2021, the country had a Human Development Index (HDI) score of 0.477[xvii], placing it 181stout of 191 countries published on the list; and whilst health professionals in the country are justifiably prioritising their focus on the country’s high rates of infant mortality, there has been a lack of attention paid to the fragile psychological state of the country’s ex-child soldiers who were active in the 90s.

Research by Theresa Betancourt, the leading expert on Sierra Leone’s child soldiers, found that ex-child recruits in the country are experiencing high levels of trauma since the conflict ended in 2002. Of those children who had joined armed groups, 63% had witnessed violent death; 62% had been beaten by armed forces; 39% had been forced to take drugs; and 27% had killed or injured others in war[xviii]. Experiencing these kinds of atrocities at a young age can impair the development of the prefrontal cortex which affects logical thinking and memory. This can contribute to a greater risk of suffering from depression and anxiety among war-exposed youths as they disassociate their feelings from their experiences and therefore struggle to logically tackle social encounters when the feelings resurface in later life. These, in turn, impact other areas of life such as finances, attachment and social interaction – especially when there are lasting stigmas attached to their actions whilst in service.

Multiple other external stressors influence how individuals behave post-conflict. Perceived stigmas from external actors play a massive role in how ex-child soldiers perceive themselves and measure their self-worth. It also limits their opportunities to socialise as other actors do not accept or accommodate them in a way that allows them to reintegrate into mainstream society. This can ultimately result in individuals retreating to the fringes of civilisation so as not to feel judged. But this reinforces their perceptions of themselves and how they feel society views them and amplifies the potential spiral of an individual’s mental health.

But despite the odds stacked against them, the rehabilitation and reintegration of child soldiers back into mainstream society is possible. Evidence suggests that despite the trauma many ex-child soldiers live with resulting from the numerous ACEs they have experienced, positive developmental outcomes are achievable if the right resources and support available[xix]. There is a multitude of humanitarian aid and support that incorporates holistic trauma-led approaches to helping children after wartime that can and do help children who have actively participated in conflicts.

The United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone set out a peacebuilding mandate that focussed on the demobilisation, disarmament, and reintegration of child soldiers’ post-civil conflict. The agency disarmed 75,000 ex-fighters, many of whom were children and in efforts to promote peace, alongside other UN agencies, set up numerous projects to provide jobs to thousands of unemployed youths rebuilding schools, medical centres and more[xx]. Most importantly, the projects provided a safe space overseen by UN peacekeepers where young children involved in fighting could reintegrate into wider society without the stresses or stigmas that may have otherwise been present if excluded.

More generally across the world, UNICEF, commissioned by the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, provides psychological support during this transition period. They run courses on sensitisation and reconciliation efforts so that children can cognitively process what they have experienced and begin to live with the trauma they may possess.[xxi]. Furthermore, once children have completed these courses, some programmes attempt to reunite them with their families so that they can receive the love, support and attachment that is so desperately needed to promote stability and good mental well-being.

There are also many other NGOs acting to combat the impact of ACEs on ex-child soldiers. The Children and War Foundation is a non-profit organisation that helps children in communities that were previously affected by war. They have developed numerous study-proven interventions and support groups for ex-child soldiers to discuss their experiences and develop coping strategies in life after war. War Child is another agency that does similar work but also additionally runs multiple rehabilitation programmes for children suffering from drug addiction as a result of doping in armed militia groups that aim to reduce their reliance on using and instead focus on positive growth outcomes.

It must be noted that the rehabilitation of ex-child soldiers is highly gendered and whilst the above services are available for both genders, young women and girls face additional challenges when reintegrating back into wider society – especially when they have been victims of sexual abuse. 1 in 6 children in war zones are victims of sexual abuse; of that statistic, 98% are young women[xxii]. With a lack of state systems to report the crime, social stigmas, and the fear of retaliation by the perpetrator; young women can often feel extremely isolated when conflicts resolve and, like other ACEs, the impacts of the abuse can have long-lasting negative effects. UNICEF runs programmes the world over for child victims of sexual abuse. These include support for safe and accessible reporting, reliable medical support, and gender-based violence recovery sessions where both physical and mental well-being support is available for survivors living with the impacts of abuse and exploitation.

The Bigger Picture

What becomes clear is that condemning those who recruit child soldiers is not a complete solution. Children, in many instances, will fight voluntarily. And whilst in some cases this may be a desired position of status, such as for young men in Yemen; in many instances, the life of a child soldier is thrust upon its participant as a result of wider social processes. War itself alongside vulnerability, insecurity, deprivation, and poverty are all key push factors for the voluntary conscription of children into armed groups. When this is combined with the forceful nature of militia recruitment tactics, it produces a recipe for a cycle of abuse that will continue unless addressed as a whole.

The work that is being done by the UN and various other NGOs around the world to help ex-child soldiers confront the adverse experiences they encounter whilst fighting is pivotal to their rehabilitation and assimilation back into wider social practices. But if we are to prevent children from fighting in conflicts in the future, then we need to eradicate the root societal causes as well as address the post-conflict fallout whilst condemning and fighting the groups that recruit in the first place. But in a world order where ‘the original sin of humanity is its inability to live at peace’[xxiii]; will this ever be a plausible and encompassing solution?

[i] Singer, P.W. (2005). Children at War. Pantheon Books, New York.

[ii] Alvarez, J. (2020). Devshirme, the recruitment of Christian children by the Ottoman Empire to become soldiers and officials. LBV Magazine Cultural Independiente. Retrieved from: https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2020/08/devshirme-the-recruitment-of-christian-children-by-the-ottoman-empire-to-become-soldiers-and-officials/

[iii] University of Chicago. (2011). The Graphics of Revolution and War: Iranian Poster Arts Exhibition. University of Chicago Library, Chicago.

[iv] Mulroy, M. et al. (2020). Begin with the children. Child soldier numbers doubled in the Middle East in 2019. Middle East Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.mei.edu/publications/begin-children-child-soldier-numbers-doubled-middle-east-2019

[v] Nasser, A. (2023). Child Soldiers in Yemen: Cannon Fodder for an Unnecessary War. Arab Center Washington DC. Retrieved from: https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/child-soldiers-in-yemen-cannon-fodder-for-an-unnecessary-war/#:~:text=UNICEF%20reported%20at%20the%20end,have%20been%20recruited%20since%202015.

[vi] Root, T. (2013). Gun Control, Yemen-Style. The Atlantic. February, 12.

[vii] Abdullah, K. (2010). Yemen Gun Culture Harms Stability, Helps Militants. Reuters Online. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-arms-idUSTRE6B73FJ20101208

[viii] Dar Al-Salam Org. (2023) Education for Peace project. منظمة دار السلام. Retrieved from: https://peace-yemen.org.ye/?p=12757

[ix] CDC. (2023). Fast Facts: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

[x] NHS. (2023). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Attachment. Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust. Manchester.

[xi] Center on the Developing Child. (2023). What are ACEs? And how do they relate to toxic stress? Harvard University. Boston. Retrieved from: https://harvardcenter.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ACEsInfographic_080218.pdf

[xii] Young, S. (2008). The neurobiology of human social behaviour: an important but neglected topic. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. Sep; 33(5): p. 391-392.

[xiii] AACAP. (2017). Gangs and Children. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Sep; 98. Retrieved from: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-and-Gangs-098.aspx

[xiv] Betancourt, T, et al. (2020). Stigma and Acceptance of Sierra Leone’s Child Soldiers: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Adult Mental Health and Social Functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Vol. 59; No. 6: p. 715-726.

[xv] Applewhite, L., Arincorayan, D., Adams, B. (2016). Exploring the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in soldiers seeking behavioural health care during combat deployment. Military Medicine, Vol. 181; No. 10: p. 1275–1280.

[xvi] Betancourt, T. et al. (2011). Sierra Leone’s Child Soldiers: War Exposures and Mental Health Problems by Gender. J Adolesc Health. Jul; 49(1): p. 21-28.

[xvii] UNDP. (2021). Human Development Index: Explore HDI. UNDP Human Development Reports. Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI

[xviii] Harvard T.H. Chan (2011). Life after death: Helping former child soldiers become whole again. Harvard School of Public Health. Retrieved from: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/child-soldiers-betancourt/

[xix] Betancourt, T, et al. (2020). Stigma and Acceptance of Sierra Leone’s Child Soldiers: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Adult Mental Health and Social Functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Vol. 59; No. 6: p. 715-726.

[xx] UNAMSIL (2005). Sierra Leone – United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone – Background. UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Retrieved from: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unamsil/background.html

[xxi] Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General for Children and Armed Conflict. (2023). Questions and Answers on the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers. UN. Retrieved from: https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/2023/02/questions-and-answers-on-the-recruitment-and-use-of-child-soldiers2/

[xxii] Fairfield, C. (2021). One in Six Children Living in Conflict Zones at Risk of Sexual Violence by Armed Groups. Save the Children. Retrieved from: https://www.savethechildren.org/us/about-us/media-and-news/2021-press-releases/one-in-six-children-in-conflict-zones-at-risk-of-sexual-violence

[xxiii] Singer, P.W. (2006). The New Faces of War. American Educator, Winter 2005-2006.