Save The Children has published a report into the promotion and benefits of reading for all children, irrespective of geographical and cultural background.

Reading helps children to develop literary skills, improve cognitive skills and it can fire their imagination. Reading can often be entertaining, educational and engaging. It can become an important hobby, enrich a young child’s vocabulary and instil a sense of critical and emotional awareness through empathy. Moreover, reading is broadening because of its cross-cultural insights and potential.

Reading really can help to empower children in the battle against poverty

Remarkably, researchers suggest that reading for just half an hour each week can improve children’s mental wellbeing, enhancing self-esteem and confidence. In the long term, reading may even help to stave off symptoms of mental illness like dementia. There is little doubt that good literacy is potentially life-enhancing. Reading from a young age can boost future employment prospects. Good literacy from a young age can ultimately open doors to higher education which in turn can lead to better paid jobs.

How young should children begin reading?

How young should children begin reading?

Researchers believe that it is never too young to experience a child’s picture book. These are designed to be eye catching. Their storylines are often inspirational and introduce exciting, amusing, and poignant themes. In short, they help to stimulate cognitive development. So, certainly before school age it is beneficial for children to experience simple text which will help to enrich their vocabulary.

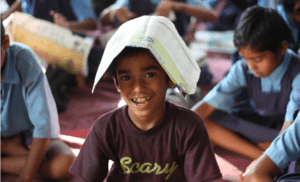

Save the Children estimate that around the world about 50% of all 3-6 year old children do not have access to preschool learning. That amounts to approximately 160 million children. Therefore, NGOs and charities are working with local communities to raise awareness of the significance of reading. Ideally, parents should be supported in encouraging their children to begin to read. If a young child enjoys looking at a book, then as she develops she is likely to embrace further opportunities to read more sophisticated material.

A lack of age-appropriate material

A lack of age-appropriate material

Early readers are in short supply in many communities. Regrettably, recent research from USAID undertaken across eleven sub-Saharan countries revealed that the biggest shortage of children’s books, written in local language, is in pre-school literature. For instance, in Nigeria, of the 500 spoken languages only six were represented through young children’s books.

Save the Children worked in four regions to attempt to increase access to high quality children’s books. In Bhutan, Cambodia, the Philippines and Rwanda, the charity has worked alongside publishers to promote and increase supplies of high quality children’s books, written in local languages. Unsurprisingly follow up research has demonstrated that an increased availability of appropriate books has led to improved levels of child literacy.

The most important catalyst

Parental interest and support for young child literacy is very important in raising reading standards. Since across the developing world many children do not spend long in class, and therefore do not spend long practising and developing reading skills at school, it is very important to promote reading to children as a leisure activity beyond a formal educational curriculum.

Steps to nurture an interest in reading beyond school

Steps to nurture an interest in reading beyond school

NGOs and charities have experimented by establishing community-based reading clubs, book buddies and book banks, where children are able to borrow and exchange reading material. Save the Children has set about promoting the benefits of children’s reading through parental workshops. The charity has also rolled out Literary Boost, a literacy programme designed to support and foster reading skills in under resourced areas.

Literary Boost led to improved letter recognition, greater fluency and confidence with basic reading, and deeper understanding of a story.

Programmes like Literary Boost help teachers too

Across the globe many teachers are not specifically trained to develop children’s reading and literary skills. Therefore, they need support and training to help effectively convey principles of literary education to young children. In Rwanda, for example, a manual was produced to advise teachers how they can teach reading skills in the most practical and effective way, given that Literary Boost is designed to target these five reading skills:

- Recognition of the alphabet and commonplace words

- Awareness of phonetics and pronunciation

- General fluency and accuracy

- Vocabulary enrichment

- Understanding context, characterisation, and themes

These key skills address the fundamental components of reading and help to ensure more accomplished literacy and comprehension.

Did Literary Boost make a uniform cross-cultural impact?

Did Literary Boost make a uniform cross-cultural impact?

As Literary Boost was implemented it became clear that it improved child literacy, irrespective of local contexts. The programme was rolled out at twelve community sites in developing countries, ranging from an urban setting in Indonesia to another in rural Ethiopia. In each one, children’s literacy improved.

Researchers conclude that reading and writing practice and development need to be conducted in a language which the children concerned understand and speak at home. While this may sound like common sense, it is important in schools where children speak different languages to make reading as child centred and specific as possible. Rich cultural contexts in classrooms are always challenging for teachers, especially in big classes.

Does speaking a minority language disadvantage children in terms of literacy?

Sadly, minority languages can marginalise a community, politically, economically and educationally. Those people who live in a linguistic minority are also disadvantaged as they attempt to find appropriate education for their children. Because children develop linguistic and literary skills through practice and everyday use, the more opportunities they have for speaking, reading and writing the greater the likely benefit. Self-esteem and confidence are also linked to developing literacy skills. If in school some children speak, read and write a different language to the one they speak at home, then they are unlikely to keep up with peers who operate in just the one language.

Moreover, opportunities for practice are most overtly beneficial to young children when they are enjoyable. Hence the undisputed links between children enjoying reading as a hobby and developing good literary skills. Research from the Literary Boost programme reveals that the more time a child can devote to reading in and out of school, the more positive the impact on their literary key skills is likely to be.

It is not just in developing countries that initiatives like this operate. For example, in the UK, Save the Children designed Families Connect, another programme which is intended to help parents when they read stories with their children.

The purpose of school reading assessments

The purpose of school reading assessments

In principle, assessments inform teachers about two important aspects of their reading schedules. First, they shed light on the developing skills and progress of each child within a particular class or year group. Second, they enable regular, evidence-led adaptation of programmes to cater better to the needs of individual children. Moreover, formalised data from schools can help to inform and shape policy makers’ decisions about revisions to the curriculum.

Conclusion: when a reading policy and programme are most effective

Save the Children’s experience is conclusive. They have found that targeting better literacy rates is most effective when they achieved an alliance between teachers, parents, and policy makers to improve opportunities for children to read. The broader range of stakeholders concerned the more impact the programme is likely to make. Essentially an acknowledged culture of reading, funded by educational budgets and steered by adaptable policies will ensure that more children learn to read well from an early age. For those children the future will be more exciting and aspirational as a result, because ultimately reading can help to empower people in the battle to defeat child poverty.