Obstacles to tackling child poverty

Across the world organisations attempting to research and roll out programmes to tackle child poverty have encountered political, economic, ethical and cultural arguments put forward to resist addressing children’s needs. This blog asks why child poverty is sometimes not promoted into the political spotlight. Here are eight reasons.

1: emotional and cultural associations

From time to time in their roles of campaigning against child poverty and implementing relief programmes, non-government organisations (NGOs) and charities like Save the Children and Oxfam have experienced political and cultural obstacles to designing policies and rolling out initiatives which are intended to tackle child poverty. A central difficulty is the emotive nature of the issue. In short, child poverty is a very sensitive matter.

A need for new approaches

At first glance this sort of sensitivity may simply seem to be uncooperative, but it is vital that its significance is appreciated and addressed for genuine progress to be made. Regrettably, it may seem all too easy for NGOs or international organisations, albeit unintentionally, to appear to antagonise political and cultural sensitivities. If there is even a hint that an organisation appears to be aiming to meddle in a political agenda, or impose what could be judged as external values in a uniform fashion across different cultures then there is little surprise that insular resentment, solidarity or even denial may be consequential. Empowering people on a national and local level to formulate campaigns to end child poverty appears to be a good way to proceed. Achieving this, however, is a hugely complex goal.

UNICEF and The Global Coalition to End Child Poverty suggest that a nuanced shift of emphasis is one possible solution. Instead of addressing child poverty per se, perhaps addressing child wellbeing may help to ease understandable concerns. A UNICEF-endorsed report concludes that ‘measures and conclusions may be similar, but it may be a more constructive way to open discussion’.

2: the overarching context

If there appears to be little political motivation to discuss, research or formulate strategies to tackle children’s circumstances specifically, then addressing in general terms the wellbeing of citizens across various communities which collectively comprise a nation may open up opportunities for some consideration of children. It is from an overarching context which focuses on people’s wellbeing that child poverty may naturally emerge as an important area of concern and so be drawn into mainstream discussions. This should open up the means to introduce new stakeholders in forming a new alliance with policy makers, in turn enabling constructive consultation, funding and planning.

3: structural issues and conflicting research programmes

From time to time organisations encounter a contrasting problem, namely, a policy designed to counter child poverty which has been enthusiastically supported in the formative stages, but lacks fully fledged research or a strong core team to coordinate its effective implementation. Perhaps different research groups have been approached to compile data but have employed different statistical methods. This could mean that any data collated would not necessarily be comparable or compatible, undermining the credibility of the initiative. Constructing multidimensional estimates of child poverty is certainly a more challenging prospect than relying on a simple financial summary based on the arbitrary poverty line of $2.15 per person per day. Appointing a single agency to oversee this vital research could mitigate potential problems. Meanwhile, assembling a purposeful, experienced and connected core team should give momentum and focus to developing, coordinating and rolling out future programmes.

4: Solutions to poverty and child poverty are very similar

If policy makers and government ministers believe that measures to tackle child poverty and poverty in general are very similar, they are likely to consider that solutions to these issues are also very similar. This means that they may see no obvious benefit in subdividing poverty as an economic, social and cultural circumstance. In that scenario, it is quite feasible that there would be little motivation to put in place initiatives to address child poverty in isolation.

However, UNICEF demonstrates that potential solutions to tackling poverty and child poverty can be surprisingly different. For example, child-centred approaches are likely to involve a questionnaire-backed consideration and analysis of the provision, support for and enrolment within education programmes and future vocational training. Ongoing and endline surveys are also vital to update progress through the production of revised data. Naturally, analysing and tackling systemic poverty will not wholly focus on child specific issues.

5: In crisis areas measuring child poverty is counterproductive

A plausible-sounding case can be made that if political and social conditions facing individual communities are fragile, or in crisis, then there is little point in attempting to collect data specific to child poverty. For example, in areas experiencing an ongoing humanitarian crisis, it is simply not a practical priority to research child poverty. Yet maintaining support for a rolling research programme which collates data on child poverty can help to clarify specific and developing circumstances and inform agencies in coordinating strategic responses to both child poverty and any ongoing emergency.

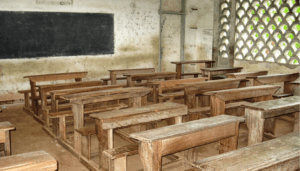

6: Prioritising child poverty only benefits children

UNICEF highlights the fact that addressing child poverty helps to tackle poverty in general. In fact an innovative way to focus on tackling poverty within society is to centralise the significance of child poverty. By addressing the circumstances, needs and rights of children, all members of their communities are likely to feel the benefit of specific policy changes. Building alliances with organisations and stakeholders whose work tackles poverty is vital and forming a coordinated agenda around child poverty helps to benefit everyone. For example, enrolling as many children as possible within education programmes will naturally lead to a better educated workforce, potentially fostering personal aspirations and opening up improved prospects.

7: Concentrating on child poverty is not the best use of resources

An argument can be made that because there are many issues facing children and young people living within culturally disparate communities in a country, child poverty is not necessarily the top priority. Perhaps healthcare or rights should be considered the pre-eminent concerns. Yet by highlighting child poverty and focussing resources on that, it is likely that support will naturally emerge for those other areas which are obviously crucial for young people’s wellbeing. An informed, holistic overview will be a likely outcome of addressing child poverty. Researching and tackling its causes can also shed light on everyone’s living standards, rights and needs.

8: The poorest households have to bear costs of research

Any research programme, policy formulation and the subsequent implementation of a new initiative need to be financed. Interested observers appreciate that such policies are not necessarily paid for by comparatively wealthy tax payers, or international donors, charities, or NGOs. If there is any suggestion that people from low socio-economic backgrounds may be obliged to fund poverty research programmes through personal taxes or even out-of-pocket expenditure, it would be vital to investigate the financing structure of policies and programmes to formulate more appropriate ways to finance direct political intervention.

Compounding the problem of poverty within communities, even with sincerely altruistic goals, is unlikely to lead to welcome, or acceptable, solutions. If the target community feels in any way resentful then such action would also be counterproductive. Before any research begins, it needs to be appropriately funded in an equitably acceptable manner, preferably through associated stakeholders. The fiscal burden cannot be borne by the poorest in the community.

Conclusions

Conclusions

Arguments and obstacles put forward against tackling child poverty arise from genuine economic, cultural, and ethical concerns. Addressing these is very important to ensure that campaigns against child poverty can be conducted effectively and in a coordinated manner. An appropriately respected core team can build constructive working relationships with researchers and key stakeholders to put in place suitable finance and a rigorous, innovative rolling programme, informed and publicised by ongoing data collection.

All discussions and planning need to be undertaken in culturally sensitive, constructive and supportive ways. Moreover, where possible the benefits of detailed analysis, research, and measurement of child poverty need to be set into a holistic context and be clearly appreciated by policy makers and other interested parties. Emerging aims and policies to address the complexities of child poverty should therefore be based on well informed agreement.