How many people are now displaced in Turkey and Syria?

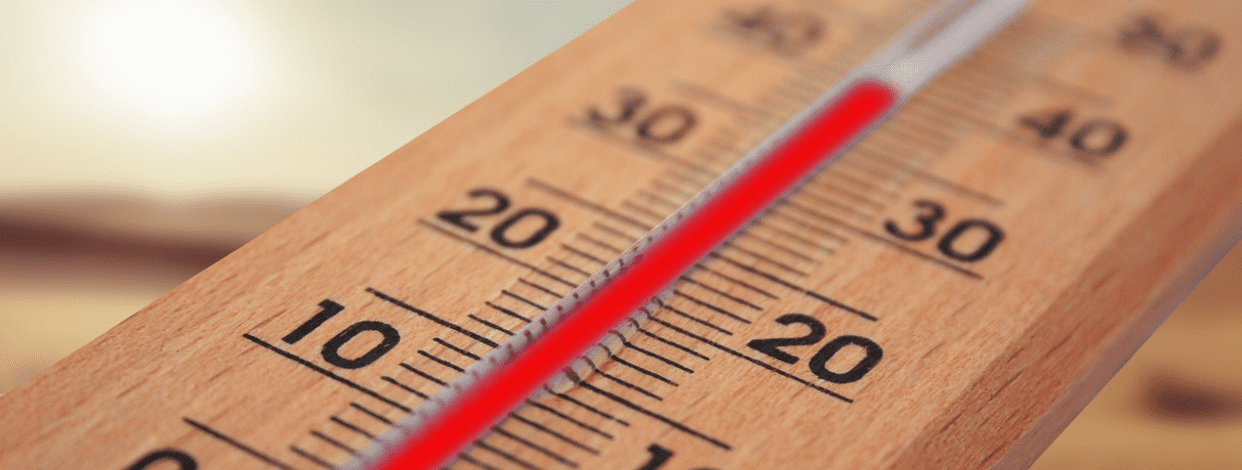

Following the devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria on February 6th, the vice-president of Turkey, Fuat Oktay, has estimated that more than a million people are presently living in official encampments. This is in a context of bitterly cold nights where temperatures have been registering lows of -9 ̊C. However, in Syria the numbers are even higher. Sivanka Dhanapala, a Syrian official speaking on behalf of the UN commissioner for refugees informed a press conference that well over 5 million people were now homeless. The UK’s Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) estimates that 17 million people are living within the overall affected area.

What has been the UK’s response to the natural disaster so far?

International humanitarian aid continues to arrive in Syria and Turkey. In the glare of harrowing media coverage, governments and charitable organisations have scrambled to be proactive in promoting, assisting and delivering relief work, and so made their own headlines. In the UK, members of the general public have generously donated over £65 million to help those who have lost so much. The UK government initially pledged a package of financial assistance of several million pounds, and aid including a 77 strong search and rescue team, life-saving equipment, medical experts, hygiene kits, tents, blankets, and loan of a Hercules transport plane. It has also made a commitment to coordinate further help with Turkey’s government, the UN working on the ground in Syria, and other international partners.

How have women and children in northwest Syria been affected?

Commentators and observers on the ground are calling the quakes a double tragedy. There were already over four million people living in northwest Syria who have lost their homes because of the ongoing war and civil unrest. Now many of these people have lost their temporary accommodation as well. The majority are children and women who have lost fathers, brothers and husbands due to the long running conflict. ActionAid has reported the comments of an emergency responder, Sawser Talostan, ‘Children do not even know the meaning of the word home because they were born in, or live in a tent, and some of them do not even know the meaning of the word school.’ Following the earthquakes there has been a complete breakdown in public services and support. Now others have lost their livelihoods and are facing more displacement. Several hours after the initial quake on February 6th people started to return to their former homes to salvage some possessions, just as the biggest quake struck (measuring 7.5 on the Richter Scale), only exacerbating the plight of many.

Why should people prioritise the safety of children and women in particular?

In the immediate, chaotic aftermath of a natural disaster, governments and non-government organisations (NGOs) prioritise rescue efforts, alongside establishing shelter, food supplies, a clean water supply, sanitation service, and further aid in the form of clothing and more general support. Keeping transport links and border crossings open is a further vital part of this process. Regrettably, in times of crises, when law and order break down, and when people lose their homes, possessions and loved ones, it is women and children who are especially vulnerable.

In such difficult conditions it is easy to overlook the fact that women and children can be left in extremely exposed circumstances. For example, without the safety and privacy afforded by their own homes and families, they may face sexual exploitation. For those who find themselves bereaved, isolated and dispossessed, the threat of coercion into prostitution can become a new and dreadful reality. Moreover, desperate young people can be lured into child labour, or slavery, by unscrupulous cartels which will simply ignore children’s rights for the sake of profit.

Such shady operatives can justify their actions as charitable, claiming that they are aiding the most destitute people in their societies by employing young people and paying them something. Yet these cartels are hardly better than criminals who work beyond the law, and ruthlessly exploit young people. UNICEF estimates that globally there are already 160 million children subjected to child labour. The natural disaster in the Middle East may tragically mean that this figure increases.

What about desperate families?

When families have run out of any means to support themselves and have lost everything, sometimes they are forced to contemplate resorting to child marriage. What if they simply cannot support their eldest daughter anymore? They could reason that she would be better off married, even as a child bride. Moreover, they may be promised a small financial incentive.

What about domestic violence?

Statistically speaking, strained personal relationships are another tragic outcome of natural disasters. The stresses and anxieties arising from such sudden, bewildering loss mean that children and women are more likely to be exposed to the threat of violence and abuse, often from within their own family. In many societies women bear the lion’s share of domestic responsibilities. This role, in times of crisis, becomes even more challenging. Many older children find themselves becoming child carers for their younger siblings, and wherever a mother is injured, incapacitated, or lost, they can suddenly become primary carers.

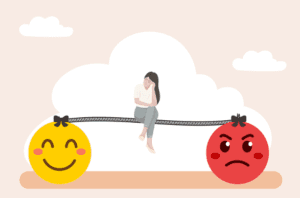

What is the impact on mental wellbeing?

These lifechanging events can take a tremendous toll on people’s mental health. It is not surprising that anyone caught up in a situation like this natural disaster is particularly prone to stress, anxiety, depression, prolonged grief and panic attacks. It is all too easy to feel abject pessimism about the future. And this is also the very moment when medical services are totally overwhelmed and disrupted.

Should more women be prominent in rolling out relief programmes?

Sabine Adi Aad, the director of ActionAid’s Arab region, argues that one way to prioritise the needs and safety of children and women caught up in the aftermath of a natural disaster is to empower more women to direct the roll out and distribution of subsequent aid programmes. Women who are instrumental in delivering support and relief will, by definition, have instinctive insight into problems and dangers facing women and children struggling in crisis hit areas. Another organisation that encapsulates this concept is Forgotten Women. They only allow women to deliver aid on the front line. This ensures that vulnerable women around the world cannot fall victim to sex for aid exploitation. By centralising the roles of women within emergency programmes, those coping with crises will immediately have advocates who can readily empathise with them. It’s an appealing proposal, and one which could benefit countless women and children in the future.

What can be done to support?

If you would like to know more about the ongoing relief programmes in Turkey and Syria, the Disasters Emergency Committee website has up to date information.